Processes, Wasserstein distance, and VC Dimension

This reading file draws various concentration results from chapter 7 and 8 of High-Dimensional Probability, and three applications of interest to be mentioned in this file are volume of polytopes, kantorovich-rubinstein duality for Wasserstein distance and VC dimension in machine learning.

Economist and Mathematician Kantorovich. Photo from St Petersburg University.

A stochastic process, or random process is a collection of $E$-valued random variables ${X_t:\Omega\to E}_{t\in T}$ with state space $(E,\mathcal{E})$ and parameter set $T$. For each $\omega\in \Omega$, let $X(\omega)$ denote the function $T\to E;t\mapsto X_t(\omega)$; then $X(\omega)$ is an element of $E^T$, the collection of all functions from $T$ to $E$. We may regard the stochastic process $(X_t)_{t\in T}$ as a random variable $X$ that takes value in the product space $(E^T,\mathcal{E}^T)$, since the map $X:\Omega\to E^T;\omega\mapsto X(\omega)$ is measurable relative to $\mathcal{D}$ and $\mathcal{E}^T$. When $T=\mathbb{N}={0,1,\cdots}$ and $(E,\mathcal{E})=(I,\mathcal{I})$ plus Markov property, we get Markov chain. In other classical settings like Brownian motion, $T=\mathbb{R}$.

For simplicity, let us assume in this file that the random process has zero mean, i.e. $$ \mathbb{E} X_t=0 \quad \text { for all } t \in T . $$ (The adjustments for the general case will be obvious.) We define the covariance function of a random process $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ as $$ \Sigma(t, s):=\operatorname{cov}\left(X_t, X_s\right)=\mathbb{E} X_t X_s, \quad t, s \in T . $$

The increments of the random process are defined as $$ d(t, s):=\left|X_t-X_s\right|_{L^2}=\left(\mathbb{E}\left(X_t-X_s\right)^2\right)^{1 / 2}, \quad t, s \in T . $$

For example, the increments of the standard Brownian motion satisfy $d(t, s)=\sqrt{t-s},; t \geq s$. The increments of a random walk with $\mathbb{E} Z_i^2=1$ satisfy $d(n, m)=\sqrt{n-m},; n \geq m$.

In high dimensional proability, it is important to go beyond the case $T=\mathbb{R}$ and allow $T$ to be a general abstract set. An important example is so-called canonical Gaussian process $$ X_t=\langle g,t\rangle,\hspace{1cm} t\in T, $$ where $T\subseteq \mathbb{R}^n$ and $g$ is a standard normal random vector in $\mathbb{R}^n$. More generally, a random process $(X_t)_{t\in T}$ is called a Gaussian process if, for any finite subset $T_0\subseteq T$, the random vector $(X_t)_{t\in T_0}$ has normal distribution. Equivalently, $(X_t)_{t\in T}$ is Gaussian if every finite linear combination $\sum_{t\in T_0}a_tX_t$ is a normal random variable. Check that the canonical Gaussian process has its increment being the Euclidean distance $\Vert t-s\Vert_2$

It is a standard exercise (HDP 7.1.8) to express the increments $\Vert X_t-X_s\Vert_{L^2}$ in terms of the covariance function $\Sigma(t,s)$ and vice versa (assuming zero r.v. belongs to the process). From the formula for multivariate normal density we may recall that the distribution of a mean zero Gaussian random vector $X$ in $\mathbb{R}^n$ is completely determined by its covariance matrix. Then, by definition, the distribution of a mean zero Gaussian process $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ is also completely determined by its covariance function $\Sigma(t, s)$. Therefore, equivalently, the distribution of the process is determined by the increments $d(t, s)$.

We list several concentration results without proof and directly go to the two applications we promised.

Theorem 7.2.1 (Slepian’s inequality). Let $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ and $\left(Y_t\right)_{t \in T}$ be two mean zero Gaussian processes. Assume that for all $t, s \in T$, we have $$ \mathbb{E} X_t^2=\mathbb{E} Y_t^2 \quad \text { and } \quad \mathbb{E}\left(X_t-X_s\right)^2 \leq \mathbb{E}\left(Y_t-Y_s\right)^2 . $$

Then for every $\tau \in \mathbb{R}$ we have the tail comparison inequality $$ \mathbb{P}\set{\sup _{t \in T} X_t \geq \tau} \leq \mathbb{P}\set{\sup _{t \in T} Y_t \geq \tau} . $$ Consequently, $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} X_t \leq \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} Y_t . $$

Whenever the tail comparison inequality holds, we say that the random variable $X$ is stochastically dominated by the random variable $Y$.

Theorem 7.2.11 (Sudakov-Fernique’s inequality). Let $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ and $\left(Y_t\right)_{t \in T}$ be two mean zero Gaussian processes. Assume that for all $t, s \in T$, we have $$ \mathbb{E}\left(X_t-X_s\right)^2 \leq \mathbb{E}\left(Y_t-Y_s\right)^2 . $$

Then $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} X_t \leq \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} Y_t . $$ Theorem 7.3.1 (Norms of Gaussian random matrices). Let $A$ be an $m \times n$ matrix with independent $N(0,1)$ entries. Then $$ \mathbb{E}|A| \leq \sqrt{m}+\sqrt{n} . $$

Magnitude of the Process: Sudakov’s Minoration Inequality and Dudley’s Inequality

Consider the mean zero Gaussian processes $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$. The increments $$ d(t, s):=\left|X_t-X_s\right|_{L^2}=\left(\mathbb{E}\left(X_t-X_s\right)^2\right)^{1 / 2} $$ define a metric on the (otherwise abstract) index set $T$, which we called the canonical metric.

The canonical metric $d(t, s)$ determines the covariance function $\Sigma(t, s)$, which in turn determines the distribution of the process $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$. So in principle, we should be able to answer any question about the distribution of a Gaussian process $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ by looking at the geometry of the metric space $(T, d)$. Put plainly, we should be able to study probability via geometry.

Let us then ask an important specific question. How can we evaluate the overall magnitude of the process, namely $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} X_t $$ in terms of the geometry of $(T, d)$ ? We will give Sudakov and Dudley’s bounds. We first recall some notions from our first note on HDP. For $\varepsilon>0$, the covering number

$$ \mathcal{N}(T, d, \varepsilon) $$ is defined to be the smallest cardinality of an $\varepsilon$-net of $T$ in the metric $d$. Equivalently, $\mathcal{N}(T, d, \varepsilon)$ is the smallest number of closed balls of radius $\varepsilon$ whose union covers $T$. Recall also that the logarithm of the covering number, $$ \log _2 \mathcal{N}(T, d, \varepsilon) $$ is called the metric entropy of $T$.

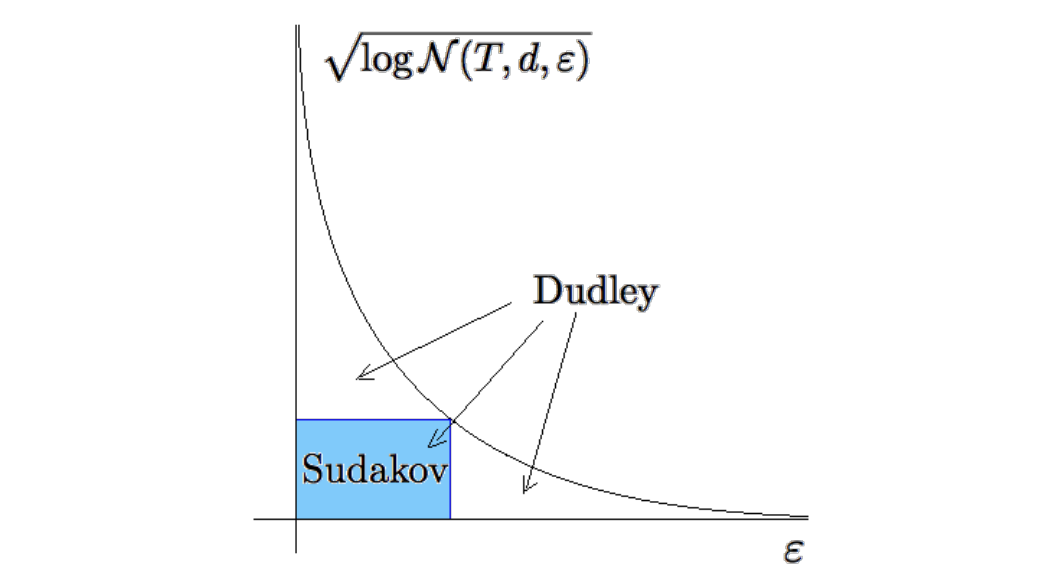

Theorem 7.4.1 (Sudakov’s minoration inequality). Let $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ be a mean zero Gaussian process. Then, for any $\varepsilon \geq 0$, we have $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} X_t \geq c \varepsilon \sqrt{\log \mathcal{N}(T, d, \varepsilon)} . $$ where $d$ is the canonical metric defined above.

Theorem 8.1.3 (Dudley’s integral inequality). Let $\left(X_t\right)_{t \in T}$ be a mean zero random process on a metric space $(T, d)$ with sub-gaussian increments. Then

$$

\mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T} X_t \leq C K \int_0^{\infty} \sqrt{\log \mathcal{N}(T, d, \varepsilon)} d \varepsilon .

$$ Sudakov’s bound by max box area; Dudley’s bound by area under curve.

Covering Numbers in $\mathbb{R}^n$ and Volume of Polytopes

Sudakov’s minoration inequality can be used to estimate the covering numbers of sets $T \subset \mathbb{R}^n$. To see how to do this, consider a canonical Gaussian process on $T$, namely $$ X_t:=\langle g, t\rangle, \quad t \in T, \quad \text { where } g \sim N\left(0, I_n\right) . $$

The canonical distance for this process is the Euclidean distance in $\mathbb{R}^n$, i.e. $$ d(t, s)=\left|X_t-X_s\right|_{L^2}=|t-s|_2 . $$ Thus Sudakov’s inequality can be stated as follows. Corollary 7.4.3 (Sudakov’s minoration inequality in $\mathbb{R}^n$ ). Let $T \subset \mathbb{R}^n$. Then, for any $\varepsilon>0$, we have $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{t \in T}\langle g, t\rangle \geq c \varepsilon \sqrt{\log \mathcal{N}(T, \varepsilon)} . $$

Here $\mathcal{N}(T, \varepsilon)$ is the covering number of $T$ by Euclidean balls - the smallest number of Euclidean balls with radii $\varepsilon$ and centers in $T$ that cover $T$, just like in our first note on HDP. Corollary 7.4.4 (Covering numbers of polytopes). Let $P$ be a polytope in $\mathbb{R}^n$ with $N$ vertices and whose diameter is bounded by 1 . Then, for every $\varepsilon>0$ we have $$ \mathcal{N}(P, \varepsilon) \leq N^{C / \varepsilon^2} . $$

Exercise 7.4.5 (Volume of polytopes). Let $P$ be a polytope in $\mathbb{R}^n$, which has $N$ vertices and is contained in the unit Euclidean ball $B_2^n$. Show that $$ \frac{\operatorname{Vol}(P)}{\operatorname{Vol}\left(B_2^n\right)} \leq\left(\frac{C \log N}{n}\right)^{C n} . $$ Soln By Proposition HDP 4.2.12, $\operatorname{Vol}(P) / \mathrm{Vol}\left(B_2^n\right) \leq \varepsilon^n \mathcal{N}(P, \varepsilon)$. By Corollary HDP 7.4.4, $\mathcal{N}(P, \varepsilon) \leq N^{C / \varepsilon^2}$. Then, taking $\varepsilon=\sqrt{2 C \log N / n}$ leads to $\operatorname{Vol}(P) / \operatorname{Vol}\left(B_2^n\right) \leq(2 \mathrm{e} C \log N / n)^{n / 2}$.

Empirical Processes and Measures and Wasserstein Distance

Suppose we want to evaluate the integral of a function $f: \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ with respect to some probability measure $\mu$ on some domain $\Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^d$ : $$ \int_{\Omega} f d \mu $$ For example, we could be interested in computing $\int_0^1 f(x) d x$ for a function $f:[0,1] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$.

We use probability to evaluate this integral. Consider a random point $X$ that takes values in $\Omega$ according to the law $\mu$, i.e. $$ \mathbb{P}{X \in A}=\mu(A) \quad \text { for any measurable set } A \subset \Omega . $$ (For example, to evaluate $\int_0^1 f(x) d x$, we take $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}[0,1]$.) Then we may interpret the integral as expectation: $$ \int_{\Omega} f d \mu=\mathbb{E} f(X) . $$

Let $X_1, X_2, \ldots$ be i.i.d. copies of $X$. The law of large numbers yields that $$ \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right) \rightarrow \mathbb{E} f(X) \quad \text { almost surely } $$ as $n \rightarrow \infty$. This means that we can approximate the integral by the sum $$ \int_{\Omega} f d \mu \approx \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right) \qquad (*) $$ where the points $X_i$ are drawn at random from the domain $\Omega$. This way of numerically computing integrals is called the Monte-Carlo method.

Can we use the same sample $X_1, \ldots, X_n$ to evaluate the integral of any function $f: \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ ? Of course, not. For a given sample, one can choose a function that oscillates in a the wrong way between the sample points, and the approximation $(*)$ will fail.

Will it help if we consider only those functions $f$ that do not oscillate wildly - for example, Lipschitz functions? It will. Our next theorem states that Monte-Carlo method $(*)$ does work well simultaneously over the class of Lipschitz functions $$ \mathcal{F}:=\set{f:[0,1] \rightarrow \mathbb{R},|f|_{\text {Lip }} \leq L}, $$ where $L$ is any fixed number.

Theorem 8.2.3 (Uniform law of large numbers). Let $X, X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n$ be i.i.d. random variables taking values in $[0,1]$. Then $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\right| \leq \frac{C L}{\sqrt{n}} . $$ The supremum over $f \in \mathcal{F}$ appears inside the expectation. By Markov’s inequality, this means that with high probability, a random sample $X_1, \ldots, X_n$ is good. And “good” means that using this sample, we can approximate the integral of any function $f \in \mathcal{F}$ with error bounded by the same quantity $C L / \sqrt{n}$. This is the same rate of convergence the classical Law of Large numbers guarantees for a single function $f$. So we paid essentially nothing for making the law of large numbers uniform over the class of functions $\mathcal{F}$.

We now come to concepts of empirical processes and measures. If we let $\mathcal{F}$ be a class of real-valued functions $f: \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ where $(\Omega, \Sigma, \mu)$ is a probability space, $X$ be a random point in $\Omega$ distributed according to the law $\mu$, and $X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n$ be independent copies of $X$. The random process $\left(X_f\right)_{f \in \mathcal{F}}$ defined by $$ X_f:=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right)-\mathbb{E} f(X) $$ is called an empirical process indexed by $\mathcal{F}$.

Consider a probability measure $\mu_n$ that is uniformly distributed on the sample $X_1, \ldots, X_n$, that is $$ \mu_n\left(\set{X_i}\right)=\frac{1}{n} \quad \text { for every } i=1, \ldots, n . $$

Note that $\mu_n$ is a random measure. It is called the empirical measure. While the integral of $f$ with respect to the original measure $\mu$ is the $\mathbb{E} f(X)$ (the “population” average of $f$ ) the integral of $f$ with respect to the empirical measure is $\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right)$ (the “sample”, or empirical, average of $f$ ). In the literature on empirical processes, the population expectation of $f$ is denoted by $\mu f$, and the empirical expectation, by $\mu_n f$ : $$ \mu f=\int f d \mu=\mathbb{E} f(X), \quad \mu_n f=\int f d \mu_n=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right) . $$

The empirical process $X_f$ thus measures the deviation of population expectation from the empirical expectation: $$ X_f=\mu f-\mu_n f . $$

The uniform law of large numbers gives a uniform bound on the deviation $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\mu_n f-\mu f\right| $$ over the class of Lipschitz functions $\mathcal{F}$.

We now use Kantorovich-Rubinstein’s duality theorem to view above deviation as Wasserstein distance between two measurs $\mu_n$ and $\mu$.

Let $(M, d)$ be a metric space that is a Polish space. For $p \in[1,+\infty]$, the Wasserstein $p$-distance between two probability measures $\mu$ and $\nu$ on $M$ with finite $p$-moments is $$ W_p(\mu, \nu)=\inf _{\gamma \in \Gamma(\mu, \nu)}\left(\mathbb{E}_{(x, y) \sim \gamma} d(x, y)^p\right)^{1 / p}, $$ where $\Gamma(\mu, \nu)$ is the set of all couplings of $\mu$ and $\nu ; W_{\infty}(\mu, \nu)$ is defined to be $\lim _{p \rightarrow+\infty} W_p(\mu, \nu)$ and corresponds to a supremum norm. A coupling $\gamma$ is a joint probability measure on $M \times M$ whose marginals are $\mu$ and $\nu$ on the first and second factors, respectively. That is, for all measurable $A \subset M$ a coupling fulfils $$ \begin{aligned} & \int_A \int_M \gamma(x, y) \mathrm{d} y \mathrm{~d} x=\mu(A), \newline & \int_A \int_M \gamma(x, y) \mathrm{d} x \mathrm{~d} y=\nu(A) . \end{aligned} $$ For $f: X \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, we define the expression $|f|_L$ by the equation $$ |f|_L=\sup {|f(x)-f(y)| / d(x, y): x, y \in X ; x \neq y} . $$

Then the Kantorovich-Rubinstein theorem states that, if the space $(X, d)$ is compact, we have $$ \inf _{\gamma \in \Gamma(\mu, \nu)} \int_{X \times X} d(x, y) d\gamma(x,y)=\sup\set{\int_X f \mathrm{~d} \mu-\int_X f \mathrm{~d} \nu:|f|_L \leq 1} $$ Therefore, if we take $p=1$, then $\mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\mu_n f-\mu f\right|$ measures the distance between $\mu_n$ and $\mu$ on spaces of measures.

VC Dimension and Machine Learning

We only briefly mention the use of high dimensional probability in ML, a relation too vast to be even properly overviewed in this file.

VC-dimension is a measure of complexity of classes of Boolean functions. By a class of Boolean functions we mean any collection $\mathcal{F}$ of functions $f: \Omega \rightarrow{0,1}$ defined on a common domain $\Omega$. We say that a subset $\Lambda \subseteq \Omega$ is shattered by $\mathcal{F}$ if any function $g: \Lambda \rightarrow{0,1}$ can be obtained by restricting some function $f \in \mathcal{F}$ onto $\Lambda$. The VC dimension of $\mathcal{F}$, denoted $\operatorname{vc}(\mathcal{F})$, is the largest cardinality of a subset $\Lambda \subseteq \Omega$ shattered by $\mathcal{F}$.

Theorem 8.3.23 (Empirical processes via VC dimension). Let $\mathcal{F}$ be a class of Boolean functions on a probability space $(\Omega, \Sigma, \mu)$ with finite $V C$ dimension $\operatorname{vc}(\mathcal{F}) \geq 1$. Let $X, X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n$ be independent random points in $\Omega$ distributed according to the law $\mu$. Then $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\right| \leq C \sqrt{\frac{\operatorname{vc}(\mathcal{F})}{n}} . $$ To do this, note that $\frac{\log N}{2 d_n}=\log \left(N^{1 / 2 d_n}\right) \leq N^{1 / 2 d_n}$.

It is easier to understand the definition of VC dimenison and various bounds should we put them in the context of machine learning, in particular, classification problem, where $\mathcal{F}$ becomes the hypothesis set. $X_1,\cdots,X_n$ are random data points. The goal is to find the optimal hypothesis $f^{*}\in \mathcal{F}$ to minimize the (quadratic) risk $$ R(f):=\mathbb{E}(f(X)-T(X))^2 $$ where $T$ is the target function. However, we don’t know this target function. The empirical risk for a function $f: \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ is defined as $$ R_n(f):=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n\left(f\left(X_i\right)-T\left(X_i\right)\right)^2 $$ Denote by $f_n^{*}$ a function in the hypothesis space $\mathcal{F}$ which minimizes the empirical risk: $$ f_n^{*}:=\arg \min _{f \in \mathcal{F}} R_n(f), $$

Note that both $R_n(f)$ and $f_n^{*}$ can be computed from the data. The outcome of learning from the data is thus $f_n^{*}$. The main question is: how large is the excess risk $$ R\left(f_n^{*}\right)-R\left(f^{*}\right) $$ Theorem 8.4.4 (Excess risk via VC dimension). Assume that the target $T$ is a Boolean function, and the hypothesis space $\mathcal{F}$ is a class of Boolean functions with finite $V C$ dimension $\operatorname{vc}(\mathcal{F}) \geq 1$. Then $$ \mathbb{E} R\left(f_n^{*}\right) \leq R\left(f^{*}\right)+C \sqrt{\frac{\operatorname{vc}(\mathcal{F})}{n}} $$ Note that $f$ tags each of the data point as either $0$ or $1$, but in practice one also need a symmetrization step to make them symmetric bernoulli.

Exercise 8.3.24 (Symmetrization for empirical processes). Let $\mathcal{F}$ be a class of functions on a probability space $(\Omega, \Sigma, \mu)$. Let $X, X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n$ be random points in $\Omega$ distributed according to the law $\mu$. Prove that $$ \mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f\left(X_i\right)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\right| \leq 2 \mathbb{E} \sup _{f \in \mathcal{F}}\left|\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \varepsilon_i f\left(X_i\right)\right| $$ where $\varepsilon_1, \varepsilon_2, \ldots$ are independent symmetric Bernoulli random variables (which are also independent of $X_1, X_2, \ldots$). Hint: Modify the proof of Symmetrization Lemma 6.4.2.