Concentration of Lipschitz Functions

The content comes from Lecture 7 of Prof. Lunde’s Math5440 and Chapter 5 of High-Dimensional Probability.

In first note on HDP, we introduced the bounded difference inequality, which is a result that can be applied to a wide range of problems. The bounded difference property may be thought of as a type of smoothness condition. Recall that a function $f: \mathbb{R}^d \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is $L$-Lipschitz if the following holds for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}^d$ , $|f(x)-f(y)| \leq L\Vert x-y\Vert $. Typically, $\Vert \cdot\Vert $ is the Euclidean norm, but one can show that the bounded difference property is a Lipschitz condition with respect to a non-standard norm (See Appendix for details).

Definition (Lipschitz functions). Let $\left(X, d_X\right)$ and $\left(Y, d_Y\right)$ be metric spaces. A function $f: X \rightarrow Y$ is called Lipschitz if there exists $L \in \mathbb{R}$ such that $$ d_Y(f(u), f(v)) \leq L \cdot d_X(u, v) \quad \text { for every } u, v \in X . $$

The infimum of all $L$ in this definition is called the Lipschitz norm of $f$ and is denoted $\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}$.

In other words, Lipschitz functions may not blow up distances between points too much. Lipschitz functions with $\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }} \leq 1$ are usually called contractions, since they may only shrink distances.

Exercise 1 (Continuity, differentiability, and Lipschitz functions). Prove the following statements. (a) Every Lipschitz function is uniformly continuous. (b) Every differentiable function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ is Lipschitz, and $$ \Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }} \leq \sup _{x \in \mathbb{R}^n}\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2 . $$ (c) Give an example of a non-Lipschitz but uniformly continuous function $f:[-1,1] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. (d) Give an example of a non-differentiable but Lipschitz function $f:[-1,1] \rightarrow$ $\mathbb{R}$.

Here are a few useful examples of Lipschitz functions on $\mathbb{R}^n$. Exercise 2 (Linear functionals and norms as Lipschitz functions). Prove the following statements. (a) For a fixed $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^n$, the linear functional $$ f(x)=\langle x, \theta\rangle $$ is a Lipschitz function on $\mathbb{R}^n$, and $\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}=\Vert \theta\Vert _2$. (b) More generally, an $m \times n$ matrix $A$ acting as a linear operator $$ A:\left(\mathbb{R}^n,\Vert \cdot\Vert _2\right) \rightarrow\left(\mathbb{R}^m,\Vert \cdot\Vert _2\right) $$ is Lipschitz, and $\Vert A\Vert _{\text {Lip }}=\Vert A\Vert $. (c) Any norm $f(x)=\Vert x\Vert $ on $\left(\mathbb{R}^n,\Vert \cdot\Vert _2\right)$ is a Lipschitz function. The Lipschitz norm of $f$ is the smallest $L$ that satisfies $$ \Vert x\Vert \leq L\Vert x\Vert _2 \quad \text { for all } x \in \mathbb{R}^n . $$ Remark:

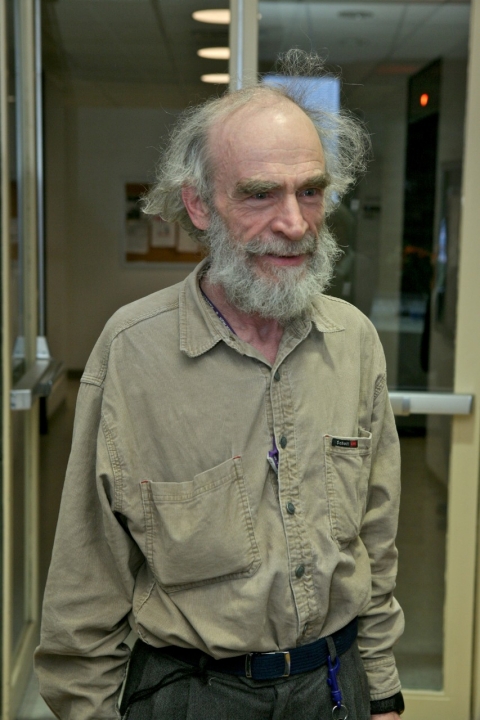

photo from NYU news

photo from NYU newsIn the preface of Metric Structures for Riemannian and Non-Riemannian Spaces, Gromov has his unifying argument about Lipschitz map for metric spaces. We quote it below:

「 What are essential maps between metric spaces? The answer “isometric” leads to a poor and rather boring category. The most generous response “continuous” takes us out of geometry to the realm of pure topology. We mediate between the two extremes by emphasizing distance decreasing maps $f: X \rightarrow Y$ as well as general $\lambda$-Lipschitz maps $f$ which enlarge distances at most by a factor $\lambda$ for some $\lambda \geq 0$.

Isomorphisms in this categeory are $\lambda$-bi-Lipschitz homeomorphisms and most metric invariants defined in our book transform in a $\lambda$-controlled way under $\lambda$-Lipschitz maps, as does for example, the diameter of a space, $\operatorname{Diam} X=\sup _{x, x^{\prime}} \operatorname{dist}\left(x, x^{\prime}\right)$. We study several classes of such invariants with a special treatment of systoles measuring the minimal volumes of homology classes in $X$ (see Ch. 4 and App. D) and of isoperimetric profiles of complete Riemannian manifolds and infinite groups which are linked in Ch. 6 to quasiconformal and quasiregular mappings.」

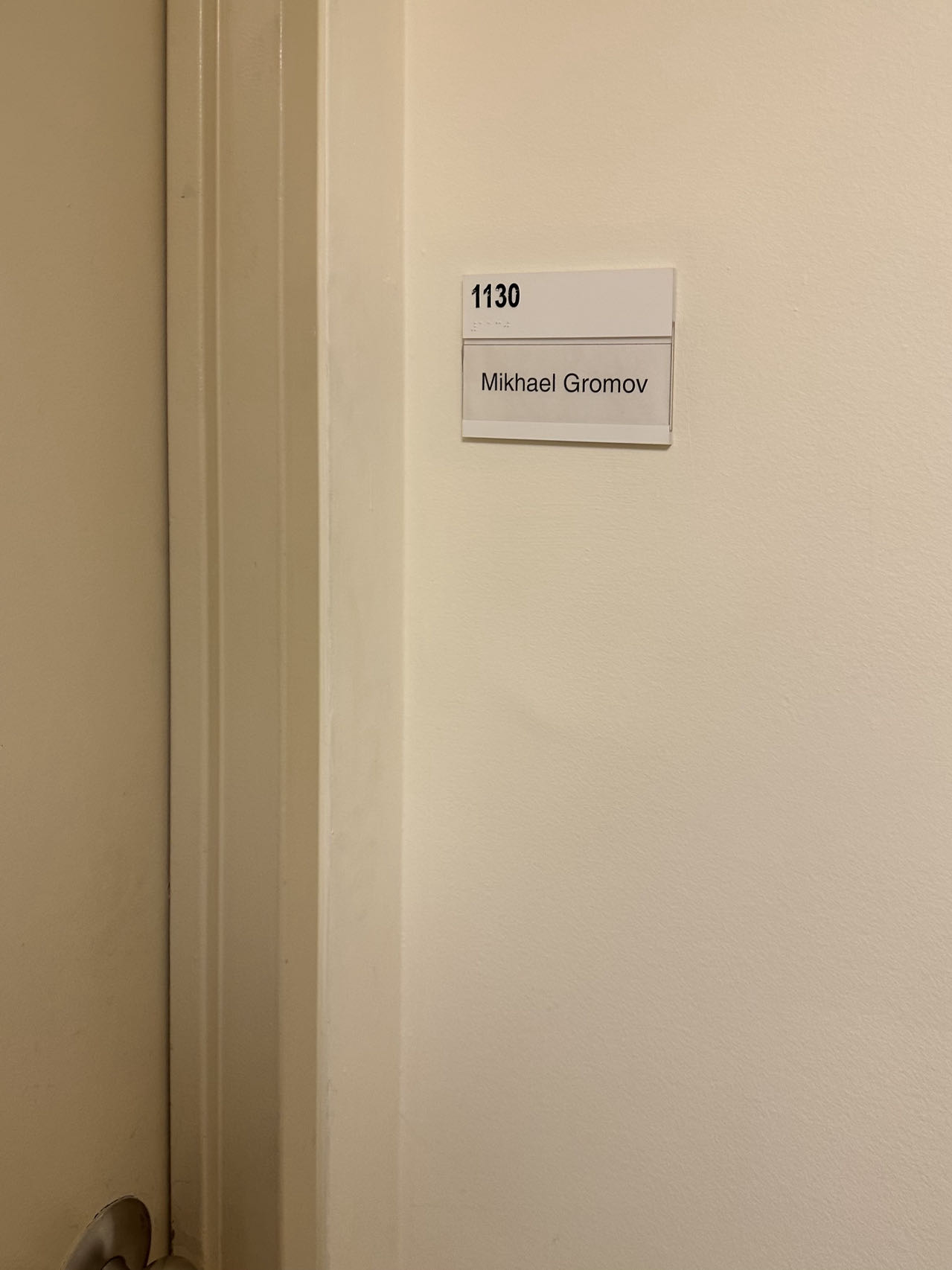

Photo at Courant institute. 3/2024.

Photo at Courant institute. 3/2024.While we focus on relating the story of concentration of Lipschitz functions, we mention two references in metric geometry: A Course in Metric Geometry by Dmitri Burago, Sergei Ivanov, and Yuri Burago, and Takashi Shioya’s Metric Measure Geometry: Gromov’s Theory of Convergence and Concentration of Metrics and Measures.

Gaussian Lipschitz Inequality

The following result establishes concentration for functions of Normal random variables that are Lipschitz with respect to the Euclidean norm.

Theorem 1 (Gaussian Lipschitz Concentration). Suppose $X_1, \ldots, X_n$ are iid standard Gaussian random variables, and $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is L-Lipschitz with respect the Euclidean norm. Then, for all $t \geq 0$, $$ P(|f(X)-E[f(X)]| \geq t) \leq 2 \exp \left(\frac{-t^2}{2 L^2}\right) $$

Before providing a proof of a variant of the theorem (in this case, the proof itself is not very important to follow), we provide some examples in which the Gaussian Lipschitz inequality provides non-trivial concentration results.

Examples

Example 1 (Order Statistics). Given a set of observations $\left(X_1, \ldots, X_n\right)$, consider the order statistics $X_{(1)} \leq X_{(2)}, \cdots \leq X_{(n)}$ where $X_{(1)}$ represents the smallest observation in the sample $X_{(2)}$ the second smallest, and so on. Let $\left(Y_1, \ldots, Y_n\right)$ be another vector, with order statistics $Y_{(1)} \leq Y_{(2)}, \cdots \leq Y_{(n)}$. We will now show that the function $f\left(x_1, \ldots, x_n\right)=x_{(k)}$ is 1-Lipschitz for any $1 \leq k \leq n$. Now, observe that: $$ \begin{align*} |f(x_1, \ldots, x_n)-f(y_1, \ldots, y_n)| & =|x_{(k)}-y_{(k)}| & \leq \max _{1 \leq k \leq n}|x_{(k)}-y_{(k)}| \newline & \leq \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n\left(x_{(i)}-y_{(i)}\right)^2} \newline & \leq\Vert x-y\Vert _2 \end{align*} $$

In the third line, we used the property that the maximum is always less than the $L_2$ norm. In the last line, we used the fact that if we are free to choose permutations acting on both the original $x$ and $y$, the one that minimizes the $L_2$ distance between the two is one in which $x$ and $y$ are each sorted in ascending (or descending) order (see Rearrangement inequality). Therefore, the order statistics use the “optimal ordering,” so the original distance between $x$ and $y$ must be larger or equal to the sorted distance.

Applying the Gaussian Lipschitz inequality, if $X_1, \ldots, X_n \sim N(0,1)$, we have: $$ P\left(\left|X_{(k)}-E\left[X_{(k)}\right]\right| \geq t\right) \leq 2 \exp \left(\frac{-t^2}{2}\right) $$ Example 2 (Gaussian Complexity). Suppose that we want to measure the complexity of a collection of vectors $\mathcal{A}$, where each vector in the set takes values in $\mathbb{R}^n$. For example, $\mathcal{A}$ could consist of a finite number of vectors, or it could be the uncountable collection in which each coordinate takes values in $[0,1]$. One way of measuring the complexity of the set is given by the Gaussian complexity: $$ Z=\sup _{a \in \mathcal{A}}\left|\sum_{i=1}^n a_i W_i\right|=\sup _{a \in \mathcal{A}}|\langle a, W\rangle| $$ where $W_1, \ldots, W_n$ are iid $N(0,1)$. To apply the Gaussian Lipschitz concentration inequality, we need to argue that a corresponding function is Lipschitz in the arguments corresponding to the Gaussian random variables. Observe that: $$ \begin{aligned} & \left|\sup_{a \in \mathcal{A}}\left| \sum_{i=1}^n a_i w_i\right|-\sup_{a \in \mathcal{A}}\left| \sum_{i=1}^n a_i w_i^{\prime}\right|\right| \newline & \leq \sup _{a \in \mathcal{A}}\left|\sum_{i=1}^n a_i\left(w_i-w_i^{\prime}\right)\right| \newline & \leq \sup _{a \in \mathcal{A}}\Vert a\Vert _2 \cdot\left\Vert w_i-w_i^{\prime}\right\Vert _2 \end{aligned} $$ where in the second line we viewed $f(a)=\sum_{i=1}^n a_i w_i g(a)=\sum_{i=1}^n a_i w_i^{\prime}$ as functions of $a$ and used the reverse triangle inequality with norm $\Vert f\Vert _{\infty}$. The third line follows from an application of the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality for each fixed $a \in \mathcal{A}$. Since for each fixed a we have this upper bound, it must follow that the supremum over the collection of upper bounds must be larger. Therefore, it follows that the Lipschitz constant is given by: $$ \mathcal{D}(\mathcal{A})=\sup _{a \in \mathcal{A}}\Vert a\Vert _2 $$ where $\mathcal{D}(\mathcal{A})$ is known as the Euclidean length of the set.

Example 3 (Eigenvalues). Let $M$ be a symmetric $n \times n$ matrix in which the entries on the upper diagonal are independent $N(0,1)$ (the lower diagonal is identical). Suppose the eigenvalues are ordered by magnitude; that is the ith eigenvalue/eigenvector pair satisfies: $$ M v_i=\lambda_i v_i $$ where $\left|\lambda_1\right| \geq \cdots\left|\lambda_i\right| \cdots \geq\left|\lambda_n\right|$ (the choice of ordering here is not crucial, but we pick one that is easy to express). For any $n \times n$ matrices $A, B$, Weyl’s inequality implies that, for any $1 \leq i \leq n:^1$ $$ \begin{aligned} \left|\lambda_i(A)-\lambda_i(B)\right| & \leq\Vert A-B\Vert _F \newline & =\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{i=1}^n\left(A_{i j}-B_{i j}\right)^2} \newline & \leq \sqrt{2 \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=i}^n\left(A_{i j}-B_{i j}\right)^2} \end{aligned} $$ where above $\Vert \cdot\Vert _F$ stands for the Frobenius norm of a matrix. Therefore, it follows that $\lambda_i(M)$ is $\sqrt{2}$-Lipschitz with respect to the Euclidean norm of the elements in the upper diagonal and we have: $$ P\left(\left|\lambda_i(M)-E\left[\lambda_i(M)\right]\right| \geq t\right) \leq 2 \exp \left(\frac{-t^2}{4}\right) $$

Proof Sketch of the Gaussian Lipschitz Inequality

We now return to providing a proof of the Gaussian Lipschitz inequality. Following the monograph by Wainwright, we prove a version of the theorem in which the constant is not sharp for simplicity. Part of the proof will involve machinery that we have seen (i.e. derive exponential concentration from MGF bounds), but a technical lemma will be needed to get an appropriate bound on the MGF. The proof of the lemma uses both the convexity assumption and a rotational invariance property of the Normal distribution to derive a bound that involves another independent Gaussian random variable $Y$.

We introduce this technical lemma without proof (for a proof see Section 2.3 of Wainwright’s monograph) before proving the theorem.

Lemma 1. Suppose that $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is differentiable. Then for any convex function $\phi$, $$ E[\phi(f(X)-E[f(X)])] \leq E\left[\phi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\langle\nabla f(X), Y\rangle\right)\right] $$ where $X$ and $Y$ are independent $N\left(0, I_n\right)$ random vectors. Now, with this result, we prove a version of Theorem 1. Before proceeding, it should be noted that Lipschitz functions are differentiable everywhere excluding a measure zero set (this is a result from measure theory/analysis). Since the Gaussian distribution is continuous, we don’t have to worry about pathological cases where the distribution puts non-zero mass on these points of non-differentiability and we can operate on the set of probability 1 for which the derivative exists ${ }^2$. Since $x \mapsto e^{\lambda x}$ is a convex function, we have:

Now, with this result, we prove a version of Theorem 1 . Before proceeding, it should be noted that Lipschitz functions are differentiable everywhere excluding a measure zero set (this is a result from measure theory/analysis). Since the Gaussian distribution is continuous, we don’t have to worry about pathological cases where the distribution puts non-zero mass on these points of non-differentiability and we can operate on the set of probability 1 for which the derivative exists ${ }^2$. Since $x \mapsto e^{\lambda x}$ is a convex function, we have: $$ \begin{aligned} E[\exp (\lambda[f(X)-E[f(X)])] & \leq E\left[\exp \left(\frac{\lambda \pi}{2}\langle Y, \nabla f(X)\rangle\right)\right] \newline & =E\left[E\left[\left.\exp \left(\frac{\lambda \pi}{2} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\partial f(x)}{\partial x_i} \cdot Y_i\right) \right\rvert, X=x\right]\right] \newline & =E\left[\exp \left(\frac{\lambda^2 \pi^2}{8}\Vert \nabla f(X)\Vert _2^2\right)\right] \end{aligned} $$

In the second line, we took law of iterated expectation with respect to $X$; since $X$ and $Y$ are independent, this is the same as fixing $X$ in the inner expectation.

Once $\left(x_1, \ldots, x_n\right)$ are fixed, we then notice that the inner product (which is a sum) is in fact still a Normal distribution because it is a sum of independent Normal distributions. The variance of the sum is $\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2^2$. Since this is a Gaussian random variable, we set $\lambda^{\prime}=\frac{\lambda \pi}{2}$ and view this quantity as the MGF of a Gaussian distribution with variance $\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2^2$.

Now, one issue that remains is interpreting this expectation. Using the fact that the Lipschitz constant is an upper bound for the norm of the gradient (see Appendix for details), we now have: $$ E\left[\exp (\lambda[f(X)-E[f(X)])] \leq \exp \left(\frac{\lambda^2 \pi^2 L^2}{8}\right)\right. $$

This implies that the sub-Gaussian constant of $f(X)-E[f(X)]$ is $\pi L / 2$. Using the Chernoff method for (sub)-Gaussian random variables, we may conclude: $$ P(|f(X)-E[f(X)]| \geq t) \leq 2 \exp \left(\frac{-2 t^2}{\pi^2 L^2}\right) $$

Concentration for Bounded Random Variables

When random variables are not Gaussian, we typically need additional assumptions for similar concentration results. One such condition is a form of convexity. The first inequality of this type was derived based on techniques due to Michel Talagrand. Consider the following notion:

Definition 1 (Separate Convexity). A function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is separately convex if each univariate function: $$ y_k \mapsto f\left(x_1, \ldots, x_{k-1}, y_k, x_{k+1}, \ldots, x_n\right) $$ is convex for $1 \leq k \leq n$. Note that separate convexity is a weaker condition than convexity of the whole function. For some intuition, recall that if the function is twice differentiable, a univariate function is convex if and only if $f^{\prime \prime}(x) \geq 0$ for all $x$. In contrast, a twice-differentiable multivariate function is convex if and only if the Hessian matrix, defined as: $$ H_f(x)=\left[\begin{array}{cccc} \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_1^2} & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_1 \partial x_2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_1 \partial x_n} \newline \frac{\partial^f f(x)}{\partial x_2 \partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_2^2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_2 \partial x_n} \newline \vdots & \ddots & \ddots & \vdots \newline \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_n \partial x_1} & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_n \partial x_2} & \cdots & \frac{\partial^2 f(x)}{\partial x_n^2} \end{array}\right] $$ is positive semidefinite for all $x$. Recall that a symmetric matrix $A$ is positive semidefinite if for any vector $z \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we have: $$ z^T A z \geq 0 $$ If we choose the $n$ vectors of the standard basis i.e. $(1,0, \ldots, 0)$ and so forth, we recover separate convexity. Convexity in the multivariate case is much stronger, since the condition needs to hold for all vectors. We now state a concentration inequality below for separately convex, Lipschitz functions.

Theorem 2. Suppose that $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is L-Lipschitz and separately convex. Moreover, suppose that $X_1, \ldots, X_n$ are independent random variables taking values in $[a, b]$. Then, $$ P(|f(X)-E[f(X)]| \geq t) \leq 2 \exp \left(\frac{-t^2}{4 L^2(b-a)^2}\right) $$

For a proof of this result, see Section 3.1.4 of Martin J.Wainwright’s High-Dimensional Statistics.

Appendix

We now show that the bounded difference condition is equivalent to the function being 1-Lipschitz with respect to a weighted Hamming distance, defined as: $$ d_{H, c}(x, y)=\sum_{i=1}^n c_i \mathbb{1}\left(x_i \neq y_i\right) $$

In words, the weighted Hamming distance compares two vectors by checking elementwise if the coordinates are the same; if they are different, that coordinate contributes $c_i$ to the distance regardless of how close or how far $x_i$ is from $y_i$ in Euclidean distance. Now, suppose that the bounded difference condition holds with constants $c_1, \ldots, c_n$. We will show below that $f(x)$ being 1 -Lipschitz with respect to $d_{H, c}$ is equivalent to the bounded difference condition holding with constants $c_1, \ldots, c_n$.

First, we will show Lipschitz with respect to Hamming norm $\Longrightarrow$ bounded difference condition. For any vectors $\left(x_1, \ldots, x_i \ldots, x_n\right)$ and $\left(x_1, \ldots, x_i^{\prime}, \ldots, x_n\right) \in$ $\mathcal{X}$ that differ only the ith coordinate, we have that $\mid f\left(x_1, \ldots, x_i, \ldots, x_n\right)-$ $f\left(x_1, \ldots, x_i^{\prime}, \ldots, x_n\right) \mid \leq c_i$. Therefore, the bounded difference condition holds for the ith coordinate with constant $c_i$. This direction follows since the choice of coordinate was arbitrary. Now to see that the bounded difference property implies the Lipschitz property, observe that: $$ \begin{aligned} & \left|f\left(x_1, \ldots, x_n\right)-f\left(y_1, \ldots, y_n\right)\right| \newline = & \left|\sum_{i=1}^n f\left(x_1, \ldots x_i, y_{i+1}, \ldots, y_n\right)-f\left(x_1, \ldots x_{i-1}, y_i, \ldots, y_n\right)\right| \newline \leq & \sum_{i=1}^n\left|f\left(x_1, \ldots x_i, y_{i+1}, \ldots, y_n\right)-f\left(x_1, \ldots x_{i-1}, y_i, \ldots, y_n\right)\right| \newline \leq & \sum_{i=1}^n \sup _{x_1, \ldots, x_n, x_i^{\prime}}\left|f\left(x_1, \ldots x_i, x_{i+1}, \ldots, x_n\right)-f\left(x_1, \ldots x_i^{\prime}, x_{i+1}, \ldots, x_n\right)\right| \mathbb{1}\left(x_i \neq y_i\right) \newline = & \sum_{i=1}^n c_i \mathbb{1}\left(x_i \neq y_i\right) \newline = & d_{H, c}(x, y) \end{aligned} $$ We now also show that for $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ that is $L$-Lipschitz with respect to the Euclidean norm, $\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2 \leq L$. First, notice that the maximum of $|\nabla f(x) \cdot v|=|\langle\nabla f(x), v\rangle|$ over $\Vert v\Vert _2=1$ is attained by $v=\nabla f(x) /\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2$, which yields $\Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2$. Now, using this observation, we will add and subtract inside the norm and use the definition of the total derivative. Recall that the total derivative satisfies: $$ \lim _{t \rightarrow 0} \frac{|f(x+t)-f(x)-\nabla f(x) \cdot t|}{\Vert t\Vert _2}=0 $$

Now, we have that: $$ \begin{aligned} \Vert \nabla f(x)\Vert _2 & =\sup _{\Vert v\Vert _2=1}|\nabla f(x) \cdot v| \newline & =\sup _{\Vert v\Vert _2=1} \lim \sup _{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{|f(x+h v)-f(x)+\nabla f(x) \cdot h v-f(x+h v)-f(x)|}{|h|} \newline & \leq\sup_{\Vert v\Vert _2=1} \limsup_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{|f(x+h v)-f(x)|}{|h|}+\limsup _{h \rightarrow 0}\sup_{\Vert v\Vert _2=1} \frac{|\nabla f(x) \cdot h v-f(x+h v)-f(x)|}{\Vert h v\Vert _2} \newline & \leq \sup _{\Vert v\Vert _2=1} \frac{L|h| \cdot\Vert v\Vert _2}{|h|}+\limsup _{t \rightarrow 0} \frac{|\nabla f(x) \cdot t-f(x+t)-f(x)|}{\Vert t\Vert _2} \newline & \leq L \end{aligned} $$

Concentration via Isoperimetric Inequalities

The main result of this section is that any Lipschitz function on the Euclidean sphere $S^{n-1}=\set{x \in \mathbb{R}^n:\Vert x\Vert_2=1}$ concentrates well.

Theorem 1 (Concentration of Lipschitz functions on the sphere). Consider a random vector $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}\left(\sqrt{n} S^{n-1}\right)$, i.e. $X$ is uniformly distributed on the Euclidean sphere of radius $\sqrt{n}$. Consider a Lipschitz function $f: \sqrt{n} S^{n-1} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Then $$ \Vert f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq C\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }} . $$

Using the definition of the sub-gaussian norm, the conclusion of this theorem can be stated as follows: for every $t \geq 0$, we have $$ \mathbb{P}{|f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)| \geq t} \leq 2 \exp \left(-\frac{c t^2}{\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}^2}\right) . $$ To prove theorem 1 in full generality, we will argue that any non-linear Lipschitz function must concentrate at least as strongly as a linear function. To show this, instead of comparing non-linear to linear functions directly, we will compare the areas of their sub-level sets - the subsets of the sphere of the form ${x: f(x) \leq a}$. The sub-level sets of linear functions are obviously the spherical caps. We can compare the areas of general sets and spherical caps using a remarkable geometric principle - an isoperimetric inequality.

The most familiar form of an isoperimetric inequality applies to subsets of $\mathbb{R}^3$ (and also in $\mathbb{R}^n$ ):

Theorem 2 (Isoperimetric inequality on $\mathbb{R}^n$ ). Among all subsets $A \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ with given volume, the Euclidean balls have minimal area. Moreover, for any $\varepsilon>0$, the Euclidean balls minimize the volume of the $\varepsilon$-neighborhood of $A$, defined as $$ A_{\varepsilon}:=\set{x \in \mathbb{R}^n: \exists y \in A \text { such that }\Vert x-y\Vert _2 \leq \varepsilon}=A+\varepsilon B_2^n . $$

A similar isoperimetric inequality holds for subsets of the sphere $S^{n-1}$, and in this case the minimizers are the spherical caps - the neighborhoods of a single point. To state this principle, we denote by $\sigma_{n-1}$ the normalized area on the sphere $S^{n-1}$ (i.e. the $n$-1-dimensional Lebesgue measure).

Theorem 3 (Isoperimetric inequality on the sphere). Let $\varepsilon>0$. Then, among all sets $A \subset S^{n-1}$ with given area $\sigma_{n-1}(A)$, the spherical caps minimize the area of the neighborhood $\sigma_{n-1}\left(A_{\varepsilon}\right)$, where $$ A_{\varepsilon}:=\set{x \in S^{n-1}: \exists y \in A \text { such that }\Vert x-y\Vert _2 \leq \varepsilon} . $$ The isoperimetric inequality implies a remarkable phenomenon that may sound counter-intuitive: if a set $A$ makes up at least a half of the sphere (in terms of area) then the neighborhood $A_{\varepsilon}$ will make up most of the sphere. We now state and prove this “blow-up” phenomenon, and then try to explain it heuristically. In view of Theorem 1, it will be convenient for us to work with the sphere of radius $\sqrt{n}$ rather than the unit sphere.

Lemma 4 (Blow-up). Let $A$ be a subset of the sphere $\sqrt{n} S^{n-1}$, and let $\sigma$ denote the normalized area on that sphere. If $\sigma(A) \geq 1 / 2$, then, for every $t \geq 0$, $$ \sigma\left(A_t\right) \geq 1-2 \exp \left(-c t^2\right) . $$

Proof Consider the hemisphere defined by the first coordinate: $$ H:=\set{x \in \sqrt{n} S^{n-1}: x_1 \leq 0} . $$

By assumption, $\sigma(A) \geq 1 / 2=\sigma(H)$, so the isoperimetric inequality (Theorem 3) implies that $$ \sigma\left(A_t\right) \geq \sigma\left(H_t\right) . $$

The neighborhood $H_t$ of the hemisphere $H$ is a spherical cap, and we could compute its area by a direct calculation. It is, however, easier to use the observation that uniform distributino on sphere is sub-Gaussian instead, i.e., the random vector $$ X \sim \operatorname{Unif}\left(\sqrt{n} S^{n-1}\right) $$ is sub-gaussian, and $\Vert X\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq C$. Since $\sigma$ is the uniform probability measure on the sphere, it follows that $$ \sigma\left(H_t\right)=\mathbb{P}\set{X \in H_t} . $$

Now, the definition of the neighborhood implies that $$ H_t \supset\set{x \in \sqrt{n} S^{n-1}: x_1 \leq t / \sqrt{2}} . $$ (if $t \geq \sqrt{2 n}$, then $H_t=\sqrt{n} S^{n-1}$. If $t<\sqrt{2 n}$, it holds that $\left(\sqrt{n}-\sqrt{n-t^2 / 2}\right)^2+t^2 / 2 \leq t^2$). Thus $$ \sigma\left(H_t\right) \geq \mathbb{P}\set{X_1 \leq t / \sqrt{2}} \geq 1-2 \exp \left(-c t^2\right) . $$

The last inequality holds because $\left\Vert X_1\right\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq\Vert X\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq C$. Since $\sigma\left(A_t\right) \geq \sigma\left(H_t\right)$, the lemma is proved.

Remark (Zero-one law). The number $1/2$ for the area is rather arbitrary. it can be changed to any constant and even to an exponentially small quantity. The blow-up phenomenon we just saw may be quite counter-intuitive at first sight. How can a small set $A$ undergo such a dramatic transition to an exponentially large set $A_{2 t}$ under such a small perturbation $2 t$ ? (Remember that $t$ can be much smaller than the radius $\sqrt{n}$ of the sphere.) However perplexing this may seem, this is a typical phenomenon in high dimensions. It is reminiscent of zero-one laws in probability theory, which basically state that events that are determined by many random variables tend to have probabilities either zero or one.

Concentration on Other Metric Measure Spaces

Gaussian concentration

The classical isoperimetric inequality in $\mathbb{R}^n$, Theorem 2, holds not only with respect to the volume but also with respect to the Gaussian measure on $\mathbb{R}^n$. The Gaussian measure of a (Borel) set $A \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ is defined as $$ \gamma_n(A):=\mathbb{P}{X \in A}=\frac{1}{(2 \pi)^{n / 2}} \int_A e^{-\Vert x\Vert _2^2 / 2} d x $$ where $X \sim N\left(0, I_n\right)$ is the standard normal random vector in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Theorem 5 (Gaussian isoperimetric inequality). Let $\varepsilon>0$. Then, among all sets $A \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ with fixed Gaussian measure $\gamma_n(A)$, the half spaces minimize the Gaussian measure of the neighborhood $\gamma_n\left(A_{\varepsilon}\right)$.

Using the method we developed for the sphere, we can deduce from Theorem 5.2.1 the following Gaussian concentration inequality.

Theorem 6 (Gaussian concentration). Consider a random vector $X \sim N\left(0, I_n\right)$ and a Lipschitz function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ (with respect to the Euclidean metric). Then $$ \Vert f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq C\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }} $$

Hamming cube

We saw how isoperimetry leads to concentration in two metric measure spaces, namely (a) the sphere $S^{n-1}$ equipped with the Euclidean (or geodesic) metric and the uniform measure, and (b) $\mathbb{R}^n$ equipped with the Euclidean metric and Gaussian measure. A similar method yields concentration on many other metric measure spaces. One of them is the Hamming cube $$ \left({0,1}^n, d, \mathbb{P}\right), $$ It will be convenient here to assume that $d(x, y)$ is the normalized Hamming distance, which is the fraction of the digits on which the binary strings $x$ and $y$ disagree, thus $$ d(x, y)=\frac{1}{n}\left|\set{i: x_i \neq y_i}\right| . $$

The measure $\mathbb{P}$ is the uniform probability measure on the Hamming cube, i.e. $$ \mathbb{P}(A)=\frac{|A|}{2^n} \quad \text { for any } A \subset{0,1}^n . $$

Theorem 7 (Concentration on the Hamming cube). Consider a random vector $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}{0,1}^n$. (Thus, the coordinates of $X$ are independent $\operatorname{Ber}(1 / 2)$ random variables.) Consider a function $f:{0,1}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Then $$ \Vert f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq \frac{C\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}}{\sqrt{n}} . $$

This result can be deduced from the isoperimetric inequality on the Hamming cube, whose minimizers are known to be the Hamming balls - the neighborhoods of single points with respect to the Hamming distance.

Symmetric group

The symmetric group $S_n$ consists of all $n$ ! permutations of $n$ symbols, which we choose to be ${1, \ldots, n}$ to be specific. We can view the symmetric group as a metric measure space $$ \left(S_n, d, \mathbb{P}\right) . $$

Here $d(\pi, \rho)$ is the normalized Hamming distance - the fraction of the symbols on which permutations $\pi$ and $\rho$ disagree: $$ d(\pi, \rho)=\frac{1}{n}|{i: \pi(i) \neq \rho(i)}| . $$ The measure $\mathbb{P}$ is the uniform probability measure on $S_n$, i.e. $$ \mathbb{P}(A)=\frac{|A|}{n !} \quad \text { for any } A \subset S_n . $$

Theorem 8 (Concentration on the symmetric group). Consider a random permutation $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}\left(S_n\right)$ and a function $f: S_n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Then following holds: $$ \Vert f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq \frac{C\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}}{\sqrt{n}} . $$

Riemannian manifolds with strictly positive curvature

A wide general class of examples with nice concentration properties is covered by the notion of a Riemannian manifold. Since we do not assume that the reader has necessary background in differential geometry, the rest of this section is optional.

Let $(M, g)$ be a compact connected smooth Riemannian manifold. The canonical distance $d(x, y)$ on $M$ is defined as the arclength (with respect to the Riemmanian tensor $g$ ) of a minimizing geodesic connecting $x$ and $y$. The Riemannian manifold can be viewed as a metric measure space $$ (M, d, \mathbb{P}) $$ where $\mathbb{P}=\frac{d v}{V}$ is the probability measure on $M$ obtained from the Riemann volume element $d v$ by dividing by $V$, the total volume of $M$.

Let $c(M)$ denote the infimum of the Ricci curvature tensor over all tangent vectors. Assuming that $c(M)>0$, it can be proved using semigroup tools that $$ \Vert f(X)-\mathbb{E} f(X)\Vert _{\psi_2} \leq \frac{C\Vert f\Vert _{\text {Lip }}}{\sqrt{c(M)}} $$ for any Lipschitz function $f: M \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. To give an example, it is known that $c\left(S^{n-1}\right)=n-1$. Thus above inequality gives an alternative approach to concentration inequality for the sphere $S^{n-1}$. We give several other examples next.

Special orthogonal group

The special orthogonal group $\mathrm{SO}(n)$ consists of all distance preserving linear transformations on $\mathbb{R}^n$. Equivalently, the elements of $\mathrm{SO}(n)$ are $n \times n$ orthogonal matrices whose determinant equals 1 . We can view the special orthogonal group as a metric measure space $$ \left(\mathrm{SO}(n),\Vert \cdot\Vert _F, \mathbb{P}\right), $$ where the distance is the Frobenius norm $\Vert A-B\Vert _F$ and $\mathbb{P}$ is the uniform probability measure on $\mathrm{SO}(n)$. Theorem 9 (Concentration on the special orthogonal group). Consider a random orthogonal matrix $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}(\mathrm{SO}(n))$ and a function $f: \operatorname{SO}(n) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Then the concentration inequality (42) holds.

This result can be deduced from concentration on general Riemannian manifolds.

Remark (Haar measure). Here we do not go into detail about the formal definition of the uniform probability measure $\mathbb{P}$ on $\mathrm{SO}(n)$. Let us just mention for an interested reader that $\mathbb{P}$ is the Haar measure on $\mathrm{SO}(n)$ - the unique probability measure that is invariant under the action on the group. ${ }^9$

One can explicitly construct a random orthogonal matrix $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}(S O(n))$ in several ways. For example, we can make it from an $n \times n$ Gaussian random matrix $G$ with $N(0,1)$ independent entries. Indeed, consider the singular value decomposition $$ G=U \Sigma V^{\top} . $$

Then the matrix of left singular vectors $X:=U$ is uniformly distributed in $\mathrm{SO}(n)$. One can then define Haar measure $\mu$ on $S O(n)$ by setting $$ \mu(A):=\mathbb{P}{X \in A} \quad \text { for } A \subset \operatorname{SO}(n) . $$ (The rotation invariance should be straightforward - check it!)

Grassmannian

The Grassmannian, or Grassmann manifold $G_{n, m}$ consists of all $m$-dimensional subspaces of $\mathbb{R}^n$. In the special case where $m=1$, the Grassman manifold can be identified with the sphere $S^{n-1}$ (how?), so the concentration result we are about to state will include the concentration on the sphere as a special case. We can view the Grassmann manifold as a metric measure space $$ \left(G_{n, m}, d, \mathbb{P}\right) . $$

The distance between subspaces $E$ and $F$ can be defined as the operator norm $$ d(E, F)=\left\Vert P_E-P_F\right\Vert $$ where $P_E$ and $P_F$ are the orthogonal projections onto $E$ and $F$, respectively. The probability $\mathbb{P}$ is, like before, the uniform (Haar) probability measure on $G_{n, m}$. This measure allows us to talk about random m-dimensional subspaces of $\mathbb{R}^n$ $$ E \sim \operatorname{Unif}\left(G_{n, m}\right), $$

Alternatively, a random subspace $E$ (and thus the Haar measure on the Grassmannian) can be constructed by computing the column span (i.e. the image) of a random $n \times m$ Gaussian random matrix $G$ with i.i.d. $N(0,1)$ entries. (The rotation invariance should be straightforward - check it!)

Theorem 10 (Concentration on the Grassmannian). Consider a random subspace $X \sim \operatorname{Unif}\left(G_{n, m}\right)$ and a function $f: G_{n, m} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. Then the concentration inequality (42) holds.

This result can be deduced from concentration on the special orthogonal group. (For the interested reader let us mention how: one can express that Grassmannian as the quotient $G_{n, m}=S O(n) /\left(S O_m \times S O_{n-m}\right)$ and use the fact that concentration passes on to quotients.)